What is “Decaf” and how do I roast it properly?

“Death before decaf” they say.

For some, decaf coffee is directly sent from coffee hell. For others it is a vital part of their portfolio.

This article is for you if you want to know

how decaf coffee is different from other coffees,

what you want to consider when roasting,

what types of decaffeination there are, and what to look for when reading the green coffee list.

Whether you like decaf in your cup or not, your customers may love it, and you can make them happy with a good roast.

Anyone who has ever roasted decaf coffee knows that it requires a different roast than your caffeinated coffees.

There are different ways to decaffeinate coffee, that is, to remove the caffeine from the coffee as much as possible. More on this below. But one thing is the same for all methods: the bean and its structure have changed. And that’s the reason to take a closer look at it. Because: the caffeine is missing.

Well, not quite, there is still a small amount left in the bean. But it is largely absent, and this has consequences for the bean structure, which we should take a look at:

Different density: The decaffeinated bean has a different density than a bean with caffeine. This does not mean, conversely, that caffeine is very heavy and contributes significantly to the weight and density of a bean. Nevertheless, the decaffeination process also removes other components from the bean and makes it porous.

Different color: Each process of removing caffeine from the bean changes the color of the green coffee. A decaffeinated bean is dark green to dark brownish, sometimes black.

We must not be deceived by this, otherwise one or more of the following things will happen:

- The color of the raw coffee often deceives us about the density and structure of the bean. And that can have a significant impact on the energy intake.

- The surface is porous and permeable. Like an open window in your roastery. This also means that the bean cannot hold much energy. The surface area with which the bean releases water also increases.

Good to know:

The decaffeinated bean has already undergone a treatment process in the form of decaffeination. While other green coffee undergoes its first refinement with roasting, for the decaffeinated bean it is already the second treatment.

Another noteworthy difference is that the silver skin is usually missing or only partially present in decaffeinated coffee. As one stage of the decaffeination process, it is polished away and therefore cannot come off during the roasting process.

What we pay attention to in the individual phases of roasting

Here are some suggestions on what to look out for when roasting decaffeinated coffee:

Drying

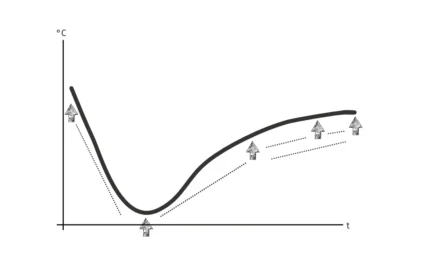

We know that our decaffeinated beans are more porous. They dry faster and don’t retain heat as well. During the drying phase, we therefore want to turn up the heat moderately so that the bean is not well roasted on the outside but practically still raw on the inside. Otherwise, this will be noticeable in the taste in the form of unpleasant, astringent acids, followed closely by roasted notes.

First crack

We should not be surprised if the first crack occurs earlier than with caffeinated beans. Overall, each roasting phase is shortened. The reason for this lies in the porosity of our bean. That is why the first crack occurs earlier. We should be prepared for this.

Development time (DEV)

We have to be very vigilant during the development time, otherwise we will end up with coffee that has reached the second crack faster than we would like. The bean is naturally more porous and softer than a caffeinated bean. Therefore, it develops faster.

Roasting by color

If we only use the visual control with the sample taker, we have to be careful not to be tempted by the uneven color of the beans to shorten the roasting process. Especially if we tend to roast a little lighter, a decaffeinated coffee can lead to heart palpitations for us (“Oops, it’s getting dark, maybe too dark…”). We think the coffee is almost ready just before the second crack and release it, even though it could have stayed in a little longer. We let the dark color fool us.

Grinding for control

Even though this step has nothing to do with the roasting itself, it still serves as a quality control. We grind the coffee after roasting and determine the exact color value. This serves to check whether the bean is roasted through or whether it is only brown on the outside and still raw on the inside.

What processes are there for decaffeinating coffee?

A brief overview and how we recognize the process in the green coffee list

To remove the caffeine from green coffee, these three steps must be observed in every process: In the first step, the green coffee is moistened or steamed; in the second step, the caffeine is removed using a solvent; and in the third step, the green coffee is dried to a residual moisture content of 10 to 12%.

There are countless ways and methods of extracting the caffeine from the raw coffee. We will only look at the most common methods here, as these are the terms we find in the lists of green coffee traders when we want to buy a decaffeinated coffee.

Decaffeination using dichloromethane (DCM)

Dichloromethane is an organic chemical solvent. It is also known as methylene chloride. As a solvent, it flows over the moistened beans and absorbs the emerging caffeine. In a further step, the caffeine is extracted from the solvent by distillation. It is now in powder form and is used in the cosmetics industry or in other products in the beverage industry. For German legislation, the residual dichloromethane content in roasted coffee must not exceed two milligrams per kilogramme.

Decaffeination using ethyl acetate

The process using ethyl acetate is the same as for dichloromethane. Ethyl acetate acts as a solvent and removes the caffeine from the wet green coffee beans. However, ethyl acetate has different properties to dichloromethane, which makes it more challenging to handle. For one thing, it is flammable and places greater demands on the equipment that uses it. The process is also known as “sugarcane”.

Decaffeination using supercritical CO2

In its supercritical state, carbon dioxide has two positive properties for decaffeination: it is as mobile as a gas and has a density like that of liquids, e.g. water. This means that it quickly and selectively removes the caffeine from the wet green coffee. Other components of the green coffee, such as lipids, remain largely in the bean.

There is also a process that uses liquid CO2, but this takes longer because less caffeine is extracted from the green coffee per cycle.

Decaffeination using water

When caffeine is dissolved in water, a caffeine-free extract is first produced. This has a special feature: it is free of caffeine but still contains the other ingredients of the raw coffee, which are normally extracted in addition to the caffeine during decaffeination. This extract is now added to the raw coffee. It only extracts the caffeine, because it is already saturated with the other ingredients, so that they remain in the raw coffee to be decaffeinated in this second step. Due to the two stages and the uneven extraction, it is a rather expensive method of decaffeination.

In the lists of green coffee traders, you will then find information such as “CO2” or “DCM” or “water”. Selling in Germany? Good to know: By law, only the processes involving CO2 and water may be used to decaffeinate organic coffee.

Is decaffeinated coffee worth including as a permanent part of your range?

5 thoughts

To answer this question, we look at the market and coffee drinkers.

Germany exports considerable quantities of decaffeinated green coffee, and this trend has been on the rise since 2016 (source: German Coffee Association, market report 2020/2021). The decaffeinated green coffee goes mainly to the USA, Spain and the Netherlands.

According to the Tchibo Coffee Report 2021, the share of decaffeinated coffee is 2.2 percent. This is a stable figure based on the last five years. Ten years ago, in 2012, the share was still 3.2 percent.

It’s up to you to decide whether decaffeinated coffee suits you and your concept. We have put together 5 thoughts that may be useful in making a decision:

#1: If you are considering adding decaffeinated coffee to your range, have samples sent to you by various green coffee dealers. Taste them and then make up your mind. Not all decaffeinated coffees are the same, and the different types of decaffeination mean that the beans differ in their sensory perception. Plus, you might have a particular coffee-growing country in mind, or a coffee with a certain certification, such as organic.

#2: If you only need decaf coffee occasionally, it may be worth buying it from a roaster friend. In our example: You have a café or a bar. Your customers occasionally ask for decaffeinated coffee. The amount is too small to roast yourself, but too large to ignore. In this case, it may be worth buying roasted decaf from a colleague.

#3: As an alternative to decaf, it may be worth taking a look at grain coffee, namely lupine coffee. This is actually caffeine-free and may be advertised as such. Some roasts are in no way inferior to a Brasil Santos and may even inspire loyal coffee drinkers.

#4: Some varieties naturally have less caffeine than others. The Laurina variety has attracted attention in this regard in recent years. Talk to your green coffee supplier about it and see what options he sees.

#5: It can be worthwhile to add a coffee to your range that is a good blend of low caffeine content and good taste. We can add a good decaffeinated coffee to half of this blend and a well-balanced caffeinated coffee to the other half (“half-half”). The customers will decide whether they want to accept the offer.

Final thoughts

Decaffeinated coffee is missing something: Of course the caffeine, but often other components of the green coffee are also removed during the process. The result is a green coffee that has already undergone a treatment before roasting. It has different characteristics, for example a different color, density and structure. These characteristics must be taken into account during roasting. The roasting phases are shortened, the coffee dries faster and reaches the first crack earlier.

Besides decaffeinated coffee, there are other ways to offer customers a coffee experience with little or even no caffeine. These include varieties that are naturally low in caffeine, blends of caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee, or lupine coffee, which can even be advertised as caffeine-free. Even though decaffeinated coffee contains remarkably little caffeine, check your domestic regulation whether it is allowed to be advertised as caffeine-free. This is because there is always a possibility that it may contain a small amount of caffeine.

Did you know?

“Caffeine-free”: applies only to grain coffee. At least in Germany. Coffee made from decaffeinated coffee beans still contains some caffeine. The law therefore prohibits the use of the term “caffeine-free” for decaffeinated coffee. The legal limit for residual caffeine is 0.1 percent. This means that decaffeinated coffee contains a maximum of 1 gram of caffeine per kilogram of dry matter.

Waxed: Some decaffeinated beans are coated with carnauba wax after cleaning. This causes the beans to flow faster through the tubes of green coffee processors and changes the pores, because the wax closes them again and thus affects the roasting behavior.

Laurina: Instead of decaf, it may be worth looking for a coffee with a naturally lower caffeine content. Laurina might be an option.

Roselius: In 1905, Ludwig Roselius of Bremen was the first person to succeed in extracting caffeine from coffee using a process of his own devising. He patented it in 1906 and launched his coffee on the market under the brand name “Kaffee Hag”.